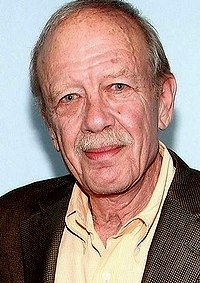

Tom Mankiewicz

d. July 31, 2010

Tom Mankiewicz, 68, a highly successful screenwriter and member of a storied movie-industry family who nonetheless was blamed by large numbers of James Bond fans for helping ruin the Bond films, died July 31 at his home in Los Angeles after a short illness. He had been treated recently for pancreatic cancer.

Mankiewicz joined the James Bond creative family in 1970 when he was hired to rewrite the script for “Diamonds Are Forever,” the seventh Bond picture and the first to be made after the sudden end of Bond’s colossal, ever-growing success throughout the 1960s. “Diamonds” revived the Bond box office and Mankiewicz stayed on to make credited and uncredited contributions throughout the 1970s.

His father was Joseph L. Mankiewicz, legendary writer-director of such films as “All About Eve,” “The Barefoot Contessa” and “A Letter to Three Wives.” His uncle Herman J. Mankiewicz won an Oscar for writing the “Citizen Kane” script with Orson Welles and went on to a string of notable credits. Other members of the family still work throughout the industry, including Tom’s brother Christopher, a film producer, and his cousin Ben, the weekend host on Turner Classic Movies.

Tom Mankiewicz was a Yale drama major who entered showbiz in 1961 as a production assistant on Michael Curtiz’s last film, “The Comancheros,” starring John Wayne. His first writing credit came on a 1966 episode of Bob Hope Presents the Chrysler Theatre. One of the actors in that show was Robert Wagner, later the star of Mankiewicz’s biggest television success, Hart to Hart. Mankiewicz billed himself as Thomas F. Mankiewicz on the Chrysler show but said later it looked so pompous on screen that he decided he’d be just Tom from then on.

His next scripts were not dramatic, however, but for variety shows produced and directed by another famous son of Hollywood, Jack Haley, Jr. Mankiewicz wrote the Emmy-winning Nancy Sinatra special “Movin’ with Nancy” (seen on NBC, Dec. 11, 1967) and “The Beat of the Brass” starring Herb Alpert and the Tijuana Brass (CBS, April 22, 1968).

In 1969, he wrote the book for “Georgy,” a Broadway musical based on the hit 1966 British film “Georgy Girl.” It closed after four performances in February 1970, but United Artists executive David Picker was among the few who saw the show during its brief run. Picker’s major concern at the time was the latest Bond film, “On Her Majesty’s Secret Service,” then still in theaters. The picture was embraced by Bond fans as one of the truly great James Bond adventures, but the broader audience was cool to the film, presumably because it lacked the gimmicks and gadgets that had become standard in previous Bonds, and almost certainly because it was the first Bond picture to be made without Sean Connery in the starring role.

UA and Bond producers Harry Saltzman and Cubby Broccoli decided to retrench — at first going so far as to make “Diamonds Are Forever” a quasi-remake of “Goldfinger,” with Gert Frobe returning as Goldfinger’s diamond-loving twin brother — while Picker launched an all-out campaign to bring Connery back to the fold. Veteran Bond screenwriter Richard Maibaum turned in a final script, minus the twin-Goldfinger gimmick, but UA and the producers wanted another rewrite. Since “Diamonds” was the first Bond adventure set mostly in the United States, Broccoli decided he needed an American writer, but one who also could write in British idiom. Picker, recalling his favorable impression of “Georgy,” recommended Mankiewicz.

Mankiewicz’s script is credited with helping Connery finally decide to take the role one last time (that and the huge salary and other inducements Picker offered). Connery and successor Roger Moore both hailed Mankiewicz for writing one-liners that were among Bond’s wittiest. “He was without doubt one of the most innovative, clever and inspirational writers of the Bond films,” Moore said. Many Bond fans vehemently disagreed, but the return of Connery at least made “Diamonds” a hit. And Mankiewicz himself was well aware of the comical turn he was helping the films to take.

“I read letters in the paper saying ‘What have they done to Bond?’ and I must say I agree with them,” he said in a 1980 interview with the James Bond Fan Club magazine Bondage. “If you present people with a certain thing and they present you back with a hundred million dollars, it’s very difficult not to try and do it again. For every Bond purist around, and I use the term with respect, there are three or four who say, gimme some more, I really loved it when that car went underwater and became a boat, gimme some more, I love that stuff. So there’s that constant battle.

“I think Bond as a series of set pieces and chase sequences has played itself out,” Mankiewicz said. “I speak quite candidly as someone who is responsible for having turned it in that direction. Not that I did it myself, but that I was there as it moved in that direction, and I helped move it in that direction.

“I think Bond pushed that kind of entertainment to the limit ... you’ve had Bond as a tight, more suspenseful story, and I think it’s time to switch tack, but in no way do I want to infer that I apologize for those films,” he added.

When Maibaum decided to write and produce a TV pilot in 1972, Mankiewicz wrote “Live and Let Die” himself. It was the first Bond screenplay created with no input from another screenwriter and it consisted almost entirely, in Mankiewicz’s words, of “a series of set pieces and chase sequences.” The script used nothing from Ian Fleming’s novel but the title, the Caribbean setting and a few character names.

The finished film, Roger Moore’s first as Bond, is often derided for its flabby plot, endless chases and juvenile humor. Raymond Benson, in his book The James Bond Bedside Companion, described the film as “a situation comedy with several outdoor action scenes.” But unlike “OHMSS,” “Live and Let Die” succeeded without Connery, and Mankiewicz was quickly signed to script the next film, “The Man with the Golden Gun.”

Saltzman and Broccoli asked Maibaum to rewrite that one after Mankiewicz left it over disagreements with director Guy Hamilton, but much of Mankiewicz’s work remains throughout — not least of which is the return of the idiot redneck sheriff J.W. Pepper from “Live and Let Die,” on vacation in Thailand of all places in the world, where he just happens to run into Bond again.

“Golden Gun” in fact brought another downturn at the box office, so the next Bond screenplay, for “The Spy Who Loved Me,” is credited to Maibaum and newcomer Christopher Wood. But Mankiewicz was among a number of writers who contributed ideas and scenes to that script, as well as a polish of the final draft, and Broccoli called him back to plot the next film, 1979’s “Moonraker.” For his last Bond job, Mankiewicz helped Broccoli and director Lewis Gilbert concoct a plot that was essentially identical to “The Spy Who Loved Me,” with the ridiculous villain based in outer space instead of underwater.

While Bond was sliding downhill, the roaring success of “Star Wars” launched a blitz of big-budget fantasy pictures, including a plan to bring Superman to the screen. Guy Hamilton, who directed Mankiewicz’s Bond scripts, developed the project but left after numerous delays. Richard Donner took over and declared Hamilton’s script — from a screen story by Mario “The Godfather” Puzo of all people — too campy and much too long and unwieldy to shoot. Donner brought in Mankiewicz and the two worked hand in glove to rework the script into a less facetious story that could be filmed in one lengthy shoot, then released as two pictures, “Superman — the Movie” (1978) and “Superman II” (1981).

“I probably wouldn’t have made the movie if Tom hadn’t come on to rewrite it,” Donner told the Los Angeles Times. “He brought a sense of reality to this comic book world. He created personalities, emotion and life.” Donner insisted on giving Mankiewicz a “creative consultant” credit in the films when the Writers Guild ruled that the original writers’ credits would stand.

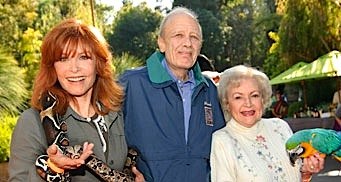

ABC TV hitmakers Aaron Spelling and Leonard Goldberg then offered Mankiewicz the chance to revamp a project for them. Sidney Sheldon had written a pilot script that Spelling thought was unworkable, about a husband and wife who were both spies. Mankiewicz turned it into Hart to Hart, with Robert Wagner and Stefanie Powers playing the couple, now obscenely rich jetsetters who make a sort of hobby out of solving the endless murders they stumble across wherever they go. Mankiewicz made his directing debut on the pilot, casting “Diamonds Are Forever” leading lady Jill St. John as a femme fatale and Clifton James, the notorious Sheriff Pepper, as another redneck cop.

“He rewrote the characters, he created the template, the design and the style of the show,” Powers told Variety. “It was an example of his wit,” she said, noting she and Mankiewicz had been friends since they were both 17. TV Guide’s critic thought the series offered viewers little more than “smooching and teasing and a witty line or two,” but Hart to Hart was another hit for Spelling and ABC. Mankiewicz stayed on to oversee the scripts and to direct a number of episodes during the show’s five-year run.

Mankiewicz could write straight adventures, as he did in his screenplays for “The Cassandra Crossing” (1977) and “The Eagle Has Landed” (also 1977), but he preferred to display a sardonic wit, as in his script for “Mother, Jugs & Speed” (1976), about a scruffy trio of ambulance drivers played by Bill Cosby, Raquel Welch and Harvey Keitel. He later turned it into a 30-minute sitcom pilot that aired on ABC in 1978 but didn’t sell.

Mankiewicz worked with Donner again on the popular 1985 fantasy film “Ladyhawke.” He also became an acknowledged if usually uncredited script doctor throughout the 80s on such films as “The Deep,” “Gremlins,” “WarGames,” “The Goonies” and “Legal Eagles.”

One of his most successful projects, both commercially and creatively, was “Dragnet,” the 1987 movie based on the famous, long-running TV series. Mankiewicz made his feature directing debut on the film and wrote the screenplay with Dan Aykroyd, who starred as Sgt. Joe Friday’s nephew, doing his patented Jack Webb impression. The picture managed to mock overblown 1980s action flicks while engaging in the usual carnage, and to send up the TV series while also paying loving respect to its well-remembered characteristics. “There’s real affection for the old show knocking around in this car-chase disaster movie,” said the Los Angeles Times review.

Mankiewicz often admitted to being intimidated by the long shadows of his father and uncle, but said his family was a close one though not necessarily “normal,” as he once told the Times: “Our idea of affection isn’t so much hugging each other as caressing each other with one-liners.”

After Tom’s death, Ben Mankiewicz told the Associated Press, “I don’t think it’s easy trying to succeed in Hollywood as a Mankiewicz, and especially as Joe Mankiewicz’s son. But Tom carved out his own sort of realm of success, and I think it was pretty impressive.”