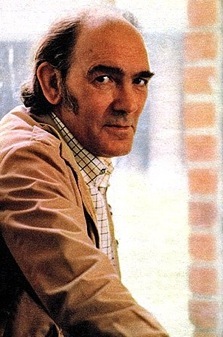

John Gardner

d. August 3, 2007

John Gardner, British author who added more titles to the James Bond series than even Bond creator Ian Fleming wrote, died Aug. 3 in Basingstoke, England. He was 80.

The Daily Mail of London reported that Gardner collapsed outside his home and died in a nearby hospital. He had been in ill health following a stroke last year.

Gardner wrote more than 50 novels in a four-decade career but gained his greatest fame, if not his highest personal satisfaction or critical acclaim, by accepting the offer to write a new series of Bond adventures.

After serving in World War II, Gardner became an Anglican priest, as his father had been, but within five years he decided he'd made a resounding error. During one Sunday sermon, as he told an interviewer, he suddenly realized “I didn't believe a word I was saying.” He left the priesthood, declared himself an agnostic and became a drama critic for the weekly newspaper in Stratford-upon-Avon. He also continued his already heavy drinking. He said later that he quit booze cold-turkey in 1959. He wrote about his battle with alcoholism in Spin the Bottle, a 1963 memoir that was his first book and his only non-fiction work.

Gardner's first novel, published in 1964, was The Liquidator, a jolly, jaundiced sendup of James Bond, who was just reaching the heights of his unprecedented popularity in print and on screen. Gardner's character, Boysie Oakes, was also employed by British Intelligence with a license to kill, but he was actually something of a coward who got sick on airplanes, abhorred violence and sub-contracted his kills to a professional hit man.

The book sold well and was filmed in 1966 with Rod Taylor as Oakes. Gardner was said to be very unimpressed with the result, but he turned out seven more Oakes novels. He started a new series in the 1970s, cheekily based on the “lost diaries” of Prof. James Moriarty, archenemy of Sherlock Holmes. Only two were published — The Return of Moriarty (1974) and The Revenge of Moriarty (1975) — before a disagreement with his publisher delayed the third.

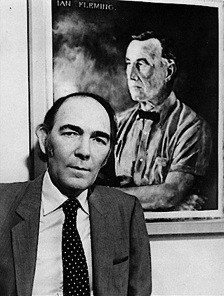

While living in Ireland as a tax exile, Gardner was approached by crime novelist and president of Britain's Detection Club Harry Keating, acting as an intermediary for Glidrose Publications, the owners of Ian Fleming's copyrights. Glidrose directors thought the time was right for Bond's return to print and said Gardner was their first choice for the job. Fleming's last novel, The Man with the Golden Gun, was published posthumously in 1965, followed by his last completed work, Octopussy and The Living Daylights, in 1966. Kingsley Amis wrote the Bond novel Colonel Sun, published in 1968, but plans to continue the books with other authors were derailed, reportedly by infighting among Glidrose directors and the heirs.

With Fleming's only son and his widow both now dead, Glidrose felt free to resume Bond's adventures but Gardner's first response was a flat refusal. “My immediate reaction was thank you but no thank you,” he explained in 2001. “I had contracts and ideas that would keep me in work for at least a decade. In fact, I wrote a letter saying very politely that I didn't think it was for me. Apart from not really liking the Bond books very much, I considered that to write more of them was a no-win situation. Kingsley Amis had done one within a few years of Ian Fleming's death and the reviews had not been wildly enthusiastic. I remembered him saying that it was a thankless task.

“But my refusal did not get mailed. Later that evening my agent telephoned and during the course of our conversation I told him about the feeler from Glidrose. There was a long pause after which he said, ‘You realize it's a great honor to be asked.’ I said yes, I knew that but the job really wasn't for me. Though I had started my career by writing comedy spy novels, I had been working for a long time on books that tried to depict the real world of the Secret Intelligence and the Security Services. Bond is fantasy, I said, the kind of fantasy that’s sometimes unpleasant. He asked me to sleep on it, saying that I was well qualified to write the books, and he finished by telling me, ‘If you don't write them they'll get somebody else.’ Later I was to find out that they indeed had a provisional list of six names and I was the first to be approached.

“There was another tenuous link between Bond and myself. In the early sixties, about two days before my first Boysie Oakes book was published, news came of Ian Fleming's death. Immediately there were press stories indicating that the cowardly B Oakes was about to take the place of Bond. He wasn't, of course, but the press are great dreamers.”

By the next morning, Gardner was starting to think of the offer as a challenge, “and I could never resist challenges even though I still had great reservations,” he noted. Within a week, he agreed to fly to London and meet with Glidrose board members. “By then I had made up my mind that I would only take on Bond if they allowed me to go about it in my own way,” Gardner said. “What I wanted to do was take the character and bring Fleming's Bond into the eighties as the same man but with all he would have learned had he lived through the sixties and seventies.

“I described to the Glidrose board how I wanted to put Bond to sleep where Fleming had left him in the sixties, waking him up now in the eighties having made sure he had not aged, but had accumulated modern thinking on the question of Intelligence and Security matters. Most of all, I wanted him to have operational know-how, the reality of correct tradecraft and modern gee-whiz technology. When I finished talking, the board gave what I can only describe as a corporate beam and said this was the way they had already decided it should go. I had satisfied the members of the Glidrose board that I was the one to do the job.”

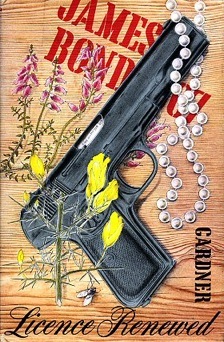

Gardner's first effort, Licence Renewed, was published in 1981. Fleming fans groused at many of the changes and the whiff of political correctness introduced, but Gardner's first several Bond novels were best-sellers in the United States — British readers and critics were less enthusiastic — and he started turning them out once a year, just as Fleming had done.

“Because I've been asked many times, I should declare that I think the best of my Bonds is The Man From Barbarossa,” Gardner wrote in 2001, referring to his tenth Bond novel. “It was also Glidrose’s favorite, but when we handed it to the American publishers they screamed in agony. ‘This isn’t the mixture as before,’ they shrieked. Which was exactly what I was aiming for.”

By 1995, Gardner matched Fleming's output of Bond books with his 14th and final Bond novel, Cold Fall. He surpassed Fleming on a technicality by also writing paperbacks based on the screenplays for "Licence to Kill" (the 1989 Bond film that was the last to star Timothy Dalton) and "Goldeneye" (the 1995 release that brought the films back with Pierce Brosnan starring). To split hairs further, Fleming wrote more individual Bond stories: 12 novels, five short stories published in For Your Eyes Only, two novelettes published in Octopussy and The Living Daylights, the short story "The Property of a Lady" added to the paperback edition of Octopussy, and the extremely short story "007 in New York" added to the American edition of Thrilling Cities, far surpassing Gardner's 14 or even 16 stories.

During his long Bond run, Gardner also turned out five much grittier spy thrillers featuring "Big Herbie" Kruger, beginning with 1979's The Nostradamus Traitor. He gave up the Bond series in 1995 after learning he had cancer of the esophagus. Glidrose immediately turned to Bond fan Raymond Benson, who wrote a further six original Bond titles as well as two more screenplay adaptations.

Gardner's cancer treatment prevented him from working for several years and left him in financial straits. He lived in the United States from 1989 to 1997 but returned to England to complete his treatment. He eventually resumed work with a new series of novels about Suzie Mountford, a female detective in World War II London. His long delayed third Moriarty book, The Redemption of Moriarty, was completed shortly before his death and will be published posthumously.

[Click here to read FYEO's 1991 review of The Man From Barbarossa.]