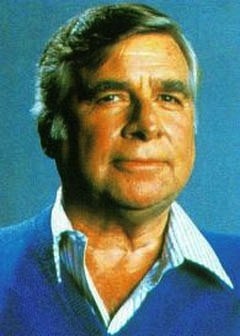

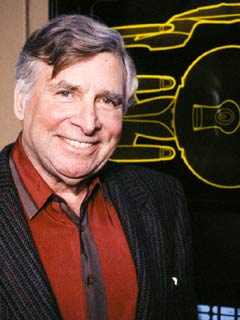

Gene Roddenberry

d. Oct. 24, 1991

The creator of the show that wouldn’t die is himself dead, from cardiac arrest caused by a massive blood clot. Months before his death on Oct. 24 at age 70, fans learned that Roddenberry had suffered a series of strokes, making it difficult for him to walk and curtailing his role as executive producer of Star Trek: The Next Generation. A Paramount spokesman said he had been ill for six weeks before his death.

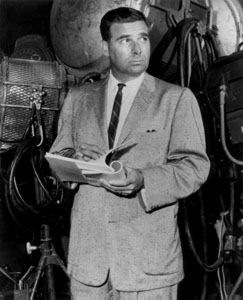

Born in 1921 in El Paso, Texas, Roddenberry was of the can-do generation of Depression children and World War II veterans. He was a fighter pilot in the Pacific theater, and continued flying after the war (for Pan Am, which died a month after he did). He also started writing for aviation magazines. In 1949, after a marriage and a plane crash, he returned to Los Angeles, where he’d grown up, to try writing for television. To make ends meet, he joined the Los Angeles Police Dept.

By 1954, Roddenberry was a police sergeant, the LAPD’s resident narcotics expert, and a moonlighting scriptwriter successful enough to quit the force for full-time writing. An award-winning script for Have Gun, Will Travel led to a steady writing job on that series, a stylized western about a high-priced troubleshooter named Paladin (played by Richard Boone), and something of a cult show in its day.

Roddenberry’s first chance to create and produce his own series came in 1963. The Lieutenant starred Gary Lockwood and Robert Vaughn as Marine Corps officers, and was made at MGM with executive producer Norman Felton. It was also the kind of straight drama that was on its way out then and lasted only one season on NBC. Vaughn, Felton and Sam Rolfe (creator of Have Gun) stayed at MGM to do The Man From U.N.C.L.E., but the studio rejected Roddenberry’s idea for a new series — about a huge spaceship exploring the galaxy — as far too difficult and expensive for TV.

Everyone knows the rest of the story. Desilu Studios, desperate to get something besides The Lucy Show on the air, welcomed Roddenberry and his impossible project (along with Bruce Geller and his equally difficult and expensive Mission: Impossible). The 1964 pilot, rejected by NBC as “too cerebral,” still proved the show could be made under TV’s constraints. Impressed network execs ordered the unprecedented second pilot, and the rest is pop culture history.

Star Trek debuted Sept. 8, 1966, with a weak episode (“The Man Trap”) that drew poor reviews, but viewers who saw what Roddenberry was up to and stuck around for the second pilot (“Where No Man Has Gone Before,” strangely not aired until the third week), “The Naked Time” and “The Menagerie” (a devilishly clever Roddenberry script combining new scenes with the series cast and extensive flashbacks using footage from the rejected pilot) were flabbergasted that something this interesting, this smart, this (yes, Mr. Spock) fascinating appeared on television every week. (By the time we’d seen “Shore Leave,” “The Squire of Gothos,” “The Devil in the Dark,” “This Side of Paradise” and “The City on the Edge of Forever,” we were enthralled.) And while the show was never a top-ten hit, neither was it the ratings disaster the myth-makers claim (not in the first season). Still, there were certain people at NBC who came to hate the show and its unusually intelligent and vocal fans. When the famous letter-writing campaign of 1968 dropped over a million pieces of mail on NBC, the network was virtually forced into renewing for a third season, but also (many fans believe) decided to kill the show once and for all.

NBC promised Roddenberry to finally give the series a decent, early-evening timeslot, then reneged, sticking it on Fridays at 10 (a notorious NBC death spot). Roddenberry had threatened to walk off the show if that happened, and to maintain some credibility, he did. Paramount, which bought out Desilu in 1967, installed the new line producer, Fred Freiberger, who didn’t have a clue what the show was about. After 24 excruciatingly awful episodes, NBC pulled the plug. By that point, sickened fans considered it a merciful death. The show became just another package of reruns, to be syndicated and eventually forgotten. And that was the end of Star Trek.

Right.

It’s ironic Roddenberry should die in the midst of Star Trek’s 25th anniversary hoopla. Or maybe it’s appropriate. Star Trek is his legacy. In the 1970s he came up with three new genre pilots — “Genesis II,” “The Questor Tapes” and “Spectre.” All were produced and aired, but no series resulted. They just weren’t as interesting as Star Trek, which grew from that package of reruns into a happily self-satisfied, we-told-you-so movement, then into a rather disconcerting, full-fledged industry. But a look at almost any episode from the series’ first year-and-a-half clearly shows why Star Trek lives on.

So will Gene Roddenberry.

Originally published in For Your Eyes Only #28.